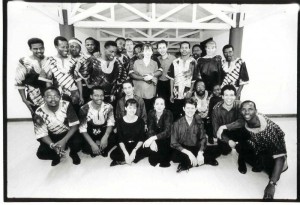

First meeting, Soweto, 1995. Photo – Ellen Elmendorp

SIMUNYE

I Fagiolini with the SDASA Chorale (Soweto)

“This remarkable record…” The Times

“Audience smiling from ear to ear with sheer pleasure.”

Business Day, South Africa

“Left seduced, enchanted and spiritually moved.”

Daily News, South Africa

Simunye is a Zulu word meaning ‘we are one’ and seemed a suitable name for this project developed by I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale of Soweto. It resulted in a CD and joint concert tours to South Africa, the UK, Scandinavia and Bermuda. Read more about the pieces and listen to music samples.

The CD is currently unavailable. Exorbitantly priced second-hand copies can be obtained from some websites. A cheaper option is to join the Friends and request it there.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmTnKTl0eSM

Introduction

Brett Pyper brought the two groups together…

Oxford is a long way from Soweto, and the distance is not only to be measured in miles. Depending on from where you are looking, the two cities represent a lot of what is both best and worst about modern history. Simunye is a way of hearing that distance that draws on the spiritual traditions of both places and captures hints and echoes of a harmonious world.

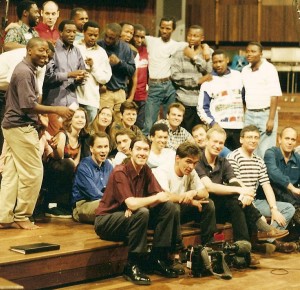

During April 1997, I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale met in South Africa for an intensive cultural exchange project to compare, contrast and combine their respective musical worlds. Although European and African vocal musics have existed alongside one another in South Africa for hundreds of years, there has been very little creative interaction between them. Free exchange between the traditions which the two groups represent has only really become possible in the post-apartheid environment, and this project celebrates a kind of dialogue that was difficult to engage in previously.

At the same time, the meeting took place in an age of extended international contact, an era in which the boundaries which define countries, cultures and musical traditions are becoming increasingly permeable. In the process, the world is becoming more uniform, as former collective identities are absorbed within an expanding global culture. Much stands to be lost in this process; countless languages, songs and ways of envisioning the world. But something new is emerging as well, and Simunye represents one attempt to give it substance: the vision of a global community in which membership does not require sameness, and difference does not mean subservience.

During their exchange project in South Africa, I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale sang at African church services, performed together in township community halls and city theatres, and spent a lot of time in workshops, developing a joint repertoire. The album Simunye: Music for a Harmonious World was a document of their meeting, and contains recordings made at a variety of locations: during a live performance at a Soweto community hall, at a township church with the congregation in attendance, in the open African bush at the resort where the workshops were held, and at a leading Johannesburg studio.

Combining different musical traditions with integrity is never easy, but I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale have proven worthy of the challenge. The groups have a number of things in common; a similar youthful membership age, comparable histories of singing together (both groups have been in existence for about thirteen years) and an infectious love of different kinds of music. But this has never eclipsed their differences; each group has remained rooted in its own musical traditions, while establishing points of contact with another musical world. Much of the original exchange project simply centred on singing for one another and responding through music, rather than in words. That spirit has remained constant as the collaboration has developed.

Most of the music in the collective repertoire expresses religious themes, as a result of the strong historical links between British and South African church music and the SDASA Chorale’s base in congregational service. Some pieces are almost as old as the musical cultures in which they originate, while others were created for or with one another. Many are statements of faith, however broadly one wishes to define it. Folksong is another important source of inspiration, as is African hymnody. The intention was not primarily to create a new musical “fusion”, and where that happened it was the result of a spontaneous sparking of ideas between the resident composers of I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale. What were important aims were the meaningful sharing of one another’s music and one another’s worlds, and a desire to cross the unproductive gap between professional and community-based music-making.

Most of the music in the collective repertoire expresses religious themes, as a result of the strong historical links between British and South African church music and the SDASA Chorale’s base in congregational service. Some pieces are almost as old as the musical cultures in which they originate, while others were created for or with one another. Many are statements of faith, however broadly one wishes to define it. Folksong is another important source of inspiration, as is African hymnody. The intention was not primarily to create a new musical “fusion”, and where that happened it was the result of a spontaneous sparking of ideas between the resident composers of I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale. What were important aims were the meaningful sharing of one another’s music and one another’s worlds, and a desire to cross the unproductive gap between professional and community-based music-making.

Since their first meeting, I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale have performed to audiences across South Africa in a variety of settings. It is now with particular pleasure that they share the fruits of their collaboration with audiences elsewhere. Thank you to all those who, over the duration of this project, have made it possible for them to span this bridge of voices across the boundaries of race, nation and culture and, in a small way, to narrow the divisions within and between human hearts from which South Africa, and our world at large, continues to emerge.

Brett Pyper

Project Co-ordinator

Atlanta, USA, February 1999

Further personal reflections

Brett Pyper: I’ve often told people that the project that became Simunye was like thinking aloud; that, for me, it was about posing the question of what it might mean to democratize South Africa’s cultural institutions and musical life. When I first articulated the question to myself, I was a junior music administrator in one of the apartheid-era provincial arts councils, ensconced in the enormous, modernist State Theatre in Pretoria’s city centre (a monument to rather than of culture, as South African composer Kevin Volans has so aptly put it). I soon realized that that particular organization was not particularly eager or equipped to respond to the question, and so by the time I Fagiolini met the SDASA Chorale in South Africa, I had left the public cultural sector and was trying my hand at project co-ordination on a freelance basis.

Seven years later, the old-style arts councils have been disbanded and replaced, the State Theatre has been closed down and then reopened, and I’m a visiting doctoral student in New York. As the collaboration between the two groups has become a chorus of other people’s musical, sociopolitical, and religious questions, I realize that I have reflected on it in writing virtually each step of the way. And so, since Robert Hollingworth has asked me for a new contribution for I Fagiolini’s website, I find myself looking over what I have been moved to write about the project over close on eight years and tracking my shifting (developing?) ideas on such questions as the merits of musical multiculturalism, South Africa’s cultural transformation, and the capacity and limitations of music in effecting social change.

Some years down the line, my critical antennae hover equivocally over an earlier statement like “Although European and African vocal musics have existed alongside one another in South Africa for hundreds of years, there has been very little creative interaction between them.” Now, I would be more inclined to point to the black South African choral tradition as a prime example of creative interaction in its own right, regardless of whether people of European descent choose to respond to it musically or not. But rather than indulging in an extended self-critique of my own existing pronouncements on the project, it seems most relevant here to point out how projects like this one are often, quite literally, a kind of thinking aloud, and that the musical expressions solidified beneath the rainbow sheen of a compact disc are necessarily a kind of sonic freeze-frame that offers a brief glimpse of this broader process.

From where I stand today, I’m inclined to feel that cross-cultural projects such as this one (or rather, “inter-cultural” projects as examples of “good cross-culturalism” are coming to be called in my current environment) are probably better at raising important questions than resolving them. For all the obvious harmony and warmth generated between I Fagiolini, the SDASA Chorale and their audiences, the project has not dispelled cultural and economic differences, but rather been based on trying to find constructive ways of working with them. Some attempts have, of course, been more successful than others. Perhaps that process, in the long run, is as or even more important than the music that such projects produce: creating a context in which people of divergent backgrounds attempt to create something together in spirit of respect and reciprocity that forces them to confront their respective preconceptions and ways of making music. Oxford may not turn out to be so far from Soweto after all; not, at least, in the ongoing cultural conversation of which this project is such an engaging example.

Roderick Williams, composer: Few compositional or arranging projects that I have been involved in have meant as much to me as this, and for a variety of reasons.

I have to admit to having been a little apprehensive about the project when it was first described to me, if only because I had no idea how the musical elements of these two such separate cultures would fit together from a purely practical viewpoint. For one, I did not understand how a group such as the SDASA Chorale could compose their music ‘democratically’ and, recognising how diverse they are culturally, even within their own group, I had misgivings about how quickly we could match our styles of music and music-making to produce anything remotely useful.

I certainly wasn’t prepared for the power and commitment of the way they perform their music. There is a strength and warmth about the SDASA Chorale that communicates across any barrier almost instantly; clearly this stems from the strength of their faith, but there is also a directness and simplicity about the music they sing and the way they deliver it that gives it tremendous force. This made our time together with the SDASA Chorale inspirational on many levels, and I am surely not alone amongst my colleagues in having been profoundly moved by the collaboration. In particular, it has affected the way I see the power of direct communication in music, and I hope it informs the way I now perform music of all sorts.

It was a particular pleasure for me to see the ‘democratic’ compositional process in action, in such pieces as ‘Ah Robin’ (track 2) and ‘Te lucis ante terminum’ (track 13); here the SDASAs developed their music in response to what we sang. They continue to develop it (and so do we) each time the two groups meet.

When I returned to England once the album recording had been completed I was again apprehensive. Although I felt that we had achieved something important, I also wondered whether the music would mean anything at all to anybody who had not been there to witness the whole process. Perhaps the whole thing would just confuse or irritate disinterested audiences. However, it is hugely gratifying that the album has found its fans all over the world and that audiences at live concerts have enjoyed the music and been engaged in the experience as much as we were in working and recording the album back in April 1997.

Robert Hollingworth, Director of I Fagiolini: If there was a single project that changed I Fagiolini, this was it. The fact that the recording didn’t go platinum (although it has sold a very respectable 17,000) is less important to us as musicians than the experience it provided. And to judge that recording as less than a success, as a few radio pundits did, because it failed to live up to their philosophical criteria of what such a meeting should produce is to devalue the process involved for the musicians who took part.

I like Brett’s description of thinking aloud. This is what happened over the four days of musical preparation for the CD in April 1997. The recording reflects that. Perhaps it would have sold more if we had experimented less and polished more, producing a stream of pieces like ‘Ah Robin’ for a more homogenous CD which people could easily hum along to. But instead, you have the raw variety of the project as it was and, rare for a CD these days, a more honest and open result.

It’s not the final word on the subject – just where we got to in the time we had. And the CD doesn’t do justice to the live performance which has been a very emotional experience for those who have shared in it, whether as singers or audiences. But it gives you a feel of the incredible buzz which we all shared while taking part.

- I was thinking that. Also @JolyonMaugham was (which carries a little more weight). https://t.co/pAu9emYdGd

- For my birthday I have done admin, walked dog, and rehearsed Walton with @The24choir https://t.co/jNTU2B3UIw https://t.co/LDhso8U9jS

- It's very reasonably priced and all those benefits.... https://t.co/DFJS8e9Dqw