Here is a further article written especially for the website by commedia dell’arte expert, Roger Savage.

The Commedia Dell’ Arte: Techniques And Tentacles

If asked to come up with a two-line history of secular comedy in the West, we might well be tempted to say that it first flourished among the ancient Greeks and Romans, then entered a long dark age, finally starting up again in the 1590s with Shakespeare and in the 1660s with Molière, says ROGER SAVAGE. But that would be to leave out important things that happened in Italy during the sixteenth century, some of which not only had a big influence on Orazio Vecchi’s Amfiparnaso (which I Fagiolini have recorded) but went on influencing theatrical, musical and visual arts right down to the present day.

Comedy as practised in the Italy of the cinquecento had two major modes: the ones later christened commedia erudita and commedia dell’arte. Commedia erudita was a scripted, literary form and often a courtly one, its plays written by respected humanist authors and acted by ‘academies’ of well-healed amateurs. Its plots were complex and its characters very diverse. (Shakespeare at the end of the century was to provide the English with a couple of scripts calling directly on the erudita tradition, his Comedy of Errors and Twelfth Night.) Commedia dell’arte — the form portrayed in L’Amfiparnaso — was rather different. True, it too might be performed at court, but it was just as likely to be seen on fit-up scaffold-stages in the public piazzas of northern Italy, especially at carnival time. It was largely performed by small touring troupes of professionals who were proud of their practical skills (hence the dell’arte in the name given to it): skills in wooing an audience, in clowning, in singing and dancing and instrument-playing, in firing off obscenities, and (for at least some of its characters) in working with comic masks. But above all in improvising, for commedia dell’arte was crucially a scriptless form. Dialogue-wise, no two shows were the same, and the actors, not limited by a text, were able to be flexible in what they offered different audiences. They could make a show short or long, boisterously broad for a crowd of unsophisticated punters in the street, subtly elegant for a courtly assembly.

Now this lack of fixed text might sound like the recipe for anarchic formlessness and a sure prescription for recurrent nervous breakdowns among actors forever on edge because they didn’t know just what might be coming next. But dell’arte performers were saved from this by three factors. First of all, each travelling troupe had its own cache of plot-scenarios. At a meeting before the show, chaired by the troupe’s capocomico or corago, the players would agree on which scenario they would be working to that day and then sort out the entrances, exits, props, songs etc. needed for its plot-line, which would most likely set up the kind of comically fruitful conflicts that were at the heart of the form: conflicts between men and women, or oldsters and youngsters, or masters and servants, or pretentious professionals and street-wise ordinary folk — or quite possibly all of these at the same time. (A lot of this material had had been purloined for the dell’arte box of tricks from commedia erudita or the classic Latin comedy of Plautus and Terence.) Attendance at the pre-show meeting was crucial. There’s a nice story of an actor who considered himself above such things, sauntering in at the very end of one and asking casually if someone could just refresh his memory of that night’s plot, only to have a bucket of recently melted snow emptied over his head with the assurance that that would refresh his memory…

Second, each member of a troupe would specialise in one particular character-type (often a type bringing with it a strong regional accent) and would repeat this role from show to show, indeed often from year to year, perhaps even making a career out of playing that particular ‘mask’. Thus the same actor in a given troupe would always play the ageing and eminently gullible Venetian merchant who was often at the centre of the action; another would be the comically inadequate ‘doctor’ (of medicine, law, music) from the varsity town of Bologna; another, a boastful army

captain (Spanish most like) — and so on, through a bright servant and a dim servant (the company’s zanni, from Bergamo perhaps), a moony boy-in-love, a cute girl-in-love etc., etc. Some characters tended to keep the same names from play to play, indeed from troupe to troupe and generation to generation. Thus the Venetian merchant was generally Pantalone, the doctor often Graziano, the bright servant quite often Arlecchino. But even those names could vary, and the names of other characters often did. Thus the Spanish captain was variously Captain Fracasso, Spavento, Cardone, Rodomonte. Rinoceronte and so on and so forth — the more super-terrifically terrifying the better. Thirdly, up his or her sleeve each actor would keep a wide range of sure-fire comic routines or lazzi — verbal, physical, musical — and would call on an appropriate one when the stage-situation looked as if it could benefit by it. For instance, a perpetually hungry servant might have (among many others) a mimed lazzo of catching flies and eating them with pepper and salt; an amorous servant a guaranteed show-stopper of a comic serenade with guitar; a dottore a penchant for singing top-of-the-pops madrigals and getting most of their words grotesquely and obscenely wrong; and the troupe’s innamorato and innamorata an especially fine Lovers’ Quarrel and Reconciliation, adaptable to all occasions. Commedia dell’arte, then, was a bit like traditional jazz or Indian classical music: improvised, yes, yet structured, built on a theme, full of tradition and premeditated device — though always making room for new ideas and personal developments.

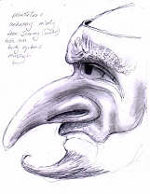

Some of these developments happened within the form itself, which had its long heyday from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth centuries. Thus, as the commedia spread down to southern Italy in the early seventeenth century, its original servant-clowns (often called Arlecchino, Mezzetino, Brighella) were joined by odder Sicilian and Neapolitan types like the unpredictable Coviello and the hunchbacked, beaky-nosed Pulliciniello. And as the form travelled over the Alps to northern Europe, new national specialisms might grow onto it. Thus a not very bright Italian character called Pedrolino became a French speciality under the name of Pierrot and set out on a life of his own in which he became a wan, sensitive, capricious-fantastic figure (the Pierrot lunaire recreated so memorably in Marcel Carné’s film Les enfants du paradis). He even crossed the Channel to join the seaside concert-party at the end of the Victorian pier. Similarly Pulliciniello/Pulcinella/Polichinelle arrived in England in marionette-commedia — a significant offshoot from the human-actor form — as Punchinello, eventually evolving into the celebrated glove puppet Mr Punch. As for the cat-like Arlecchino (later Harlequin), if you include his medieval pre-history and his nineteenth- and twentieth-century afterlife, he gets through as many lives as a cat: appearing in Dante’s Inferno, in rough commedia wearing a kaleidoscopically patched costume, later in smoother commedia wearing his famous lozenge-patterned one, then in ballet, vaudeville, pantomime, harlequinade (where else?), in operas by Busoni and Richard Strauss — even in a piece of music-theatre by Stockhausen. (‘You must live, for life is lovely’, sings Harlequin to the sad, sad heroine in Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos, summing up the clear-eyed zest and cheerful acceptingness of the commedia dell’arte generally.)

As Harlequin reveals, some of the commedia’s developments involved migrations into or appropriations by other genres and media. For instance, Continental scripted comedy in the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries quite often helped itself to situations and characters from the commedia. Molière was happy to poach from it when attempting to set up a native French comic tradition in the 1660s and ’70s; his troupe actually shared a theatre in Paris for a time with the commedia troupe of Tiberio Fiorilli, and he seems to have learned a lot from Fiorilli’s character Scaramuccia. Goldoni in the mid-eighteenth century set out to wean Italian theatre off the commedia, but not until he’d scripted a kind of preservation-in-aspic of the form in his classic Servant of two Masters; and Beaumarchais created the perfect Enlightenment Harlequin in his Figaro, the central figure in a trilogy of plays that were to generate operas by Mozart, Paisiello, Rossini, Darius Milhaud, John Corigliano and others. Then, quite understandably, the form especially attracted painters and engravers. It was the most energetic sort of spoken drama after all, full of strong presences, vivid gesture, near-balletic movement and colourful costumes, and spiced with an edge of slightly sinister caricature supplied by the masks of Pantalone, the Doctor and some of the servants. Some artists recorded the characters fairly ‘straight’, while others — Callot, Watteau, Domenico Tiepolo — took them off in rewarding directions of their own, as figures of wild energy or misty nostalgia or near-surreal fantasy. And the graphic tradition didn’t stop in 1750. Imagined snapshots of commedia characters in action can be found in Aubrey Beardsley, Pablo Picasso and David Hockney.

Similarly, commedia and commedia-connected sound-bites, or a least sonic sketches, figure in nineteenth and twentieth-century music. Think not only of Strauss and Stockhausen and those Figaro-operas but of Schumann’s Carnaval with its Pantalone, Harlequin, Columbine and Pierrot; Busoni’s Arlecchino and Stravinsky’s Pulcinella; Milhaud’s Scaramouche and Walton’s Scapino (after an engraving by Callot); the Harlequinade in Lord Berners’s Triumph of Neptune; Birtwistle’s Punch and Judy, and the very different moon-struck Pierrots in Debussy’s Cello Sonata (‘Pierrot fâché avec la lune’), Granville Bantock’s Pierrot of the Minute and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire. (Commedia lazzi can appear in seemingly quite unlikely places; isn’t Beckmesser’s garbling of the text of the Prize Song in the last act of Wagner’s Mastersingers a descendent of the dottore’s madrigal-mangling?) And these musical treatments post-1750 have precedents from the days when commedia was still a mainstream, living commercial form. To look backwards down the corridor: in the early eighteenth century, for instance, there are the purely instrumental evocations of Harlequin, Columbine, Mezzetino, Scaramouche and Pierrot in Telemann’s Ouverture burlesque, and there’s Pergolesi’s mini-opera La Serva padrona, in which a self-important pantaloon is comprehensively snared by a wily soubrette from the commedia’s tribe of Columbinas, Despinettas, Diamantinas, Franceschinas and such. In the later seventeenth century, there are the danced entries for troupes of ‘trivelins et scaramouches’ in Lully’s court-ballets and the music that Marc-Antoine Charpentier wrote for Molière’s comedy-ballet Le Malade imaginaire. This includes an interlude of a frustrated Polichinelle attempting a serenade but being persecuted by posses of fiddlers and sharpshooters, and ends with a convocation of cod-doctors conning the hypochondriac pantaloon of the title into thinking he’s been elevated to the Medical Faculty. (Cue a great deal of dottore-esque mangled Latin.) In the 1630s and ’40s the operas staged in Rome include Mazzocchi and Marazzoli’s Chi soffre speri, which has a couple of earthy commedia servants, Coviello and Zanni, weaving in and out of the romantic main plot; and the new public opera in Venice develops a similar taste for hiring commedia types to serve below stairs. And back in the 1590s and 1600s, when commedia dell’arte itself is still relatively young, the fashionable genre of the madrigal-sequence depicting modern urban life (as opposed to life in idyllic fields or steamy boudoirs) sometimes latches onto it for the whole of its subject-matter, so bringing the ‘madrigal comedy’ into being. Vecchi’s Amfiparnaso of 1597 is the biggest and arguably the best of these madrigal comedies: at once a record of the early, purely north-Italian commedia in action, a vivid piece of ‘alter-native music-theatre’ from the decade that also invented opera, and a marvellous piece of sheer musical invention. Any self-respecting comedy-troupe on the streets would have been flattered — and most likely extremely amused — to have its stock-in-trade so brilliantly rendered in sound.

- I was thinking that. Also @JolyonMaugham was (which carries a little more weight). https://t.co/pAu9emYdGd

- For my birthday I have done admin, walked dog, and rehearsed Walton with @The24choir https://t.co/jNTU2B3UIw https://t.co/LDhso8U9jS

- It's very reasonably priced and all those benefits.... https://t.co/DFJS8e9Dqw