Venetian galleys flying the standard of St.Mark engaging Turkish warships at the battle of Lepanto, 1571. (Vasari and assistants)

Further historical notes

Notes by Hugh Keyte on Lepanto, the Rosary feast, and Gabrieli’s Magnificat and In Ecclesiis.

(These notes-in-progress are multi-purpose. Some sections are of general interest, expanding the information on the CD sleeve note. Others are more detailed, and may be of use to reviewers, etc. A few sections are lengthy, dealing in merciless detail with contentious subjects such as the number of choirs in the Magnificat: these in particular will continue to be adjusted and expanded, and should eventually form the basis of a journal article.)

1612 Italian Vespers presents a reconstruction of the office of Second Vespers of the feast of Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary in some deliberately unspecified North-Italian venue. Wealthy and musically adventurous, this city-state (or whatever) we assume to have fought against the Turks at Lepanto forty-one years previously as part of the papally-summoned Holy League, and now, like all its fellow-combatants except Venice, keeps the new feast as an annual commemoration of that supposedly historic Christian victory.

For this particular Vespers service it has obtained copies of the anonymous seven-choir expanded arrangement of Gabrieli’s originally three- or four-choir Magnificat (whether from Venice or from Graz, for which the sole – and now incomplete – source was copied). From Venice it has obtained a MS copy of Gabrieli’s motet In ecclesiis (not the radically cut-down version that would appear in the posthumous Symphoniae sacrae of 1615, but the much more expansively-scored lost original, which I have attempted to restore), besides the newly published Vespers collection of the young Mantuan composer Ludovico Viadana. In the course of the Magnificat, captured Turkish banners will be paraded through the church, to the accompaniment of bells and cannon-fire without.

Lepanto

In 1569 the ag̬d Pope Pius V summoned a new crusade, a Holy League of Spanish, Roman, and Venetian forces to confront the ever-greater incursions of the Ottoman navy. Selim II had fairly recently succeeded his father Sulieman the Magnificent as Sultan, and in place of a reasonably honourable enemy the Christians of the Mediterranean now faced a passive sybarite who allowed free rein to his pitiless military commanders. A few days before the battle, news reached the fleet of the ultimate indignity. A protracted siege of Venetian forces in Famagusta (Cyprus) had ended with a Turkish guarantee of a safe passage that was savagely reneged on Рpartly because the Venetians had, among other things, slaughtered Muslim pilgrims trapped in the city whom they had undertaken to spare. The Venetian leader had his ears and nose cut off, was flayed alive, and his skin, stuffed with straw, was hung from a Turkish ship that sailed away to Constantinople, triumphantly exhibiting this grizzly trophy to the ports of Asia Minor as it passed.

Spain and Venice dominated the short-lived League, ((For different reasons, France, the Empire and Portugal did not join.)) which was intended to defend the Christian cause in perpetuity. Leading it was the 23-year-old Don Juan of Austria – despite his name a Spaniard, a natural son of Charles V, and thus half-brother of Philip II. In the two-year run-up to the battle the Venice Arsenal had turned out unprecedented numbers of galleys, each with a bow-mounted cannon, besides a few galleasses, newly invented secret weapons which were essentially monster galleys with multiple cannon firing broadside.

When the two navies met on 7th October 1571, some miles to the west of the Venetian port of Lepanto in the Gulf of Corinth, the galleasses proved too unwieldy to have much effect, but the League was favoured by the combination of a cunning Venetian ploy and a supposedly divine intervention. The traditional battering rams on the prows of the galleys had been secretly removed, so that instead of aiming to stave in the sides of the enemy craft they came up close alongside them, aided (to an extent) by a last-minute change of wind-direction, whereupon the hordes of bloodthirsty, mainly Spanish and Italian troops packed cheek-by-jowl on the Christian galleys overran the Turkish vessels, killing some 15,000, taking some 3,500 captive, and releasing around 7,500 Christian galley slaves.

The victory was hailed as a great turning-point, the breaking of a seemingly invincible enemy. In reality the Turks quickly rebuilt their navy, and the Venetians soon concluded a secret trade deal with them. But the battle continued to be celebrated as a unique victory in which God had fought on the Christian side – as he had fought with Gideon, Joshua and Sansom. In Rome, Toledo, Venice and elsewhere annual commemorative services kept the memory alive – in the case of Venice until the fall of the Republic. And there was a great outpouring of celebratory verse, painting and music: this last including motets by the Spaniard Fernando de las Infantas, and the Venetians Andrea Gabrieli and Giovanni Bassano. Particularly popular was Andrea’s Aria della battaglia for eight wind instruments, of which we incorporate a notionally busked chunk at the climactic point of our reconstructed Magnificat. At least two ‘club’ madrigal cycles by Venetian composers were published. And far away at the back of the north wind an eighteen- or nineteen-year old moderate Calvinist, King of Scotland and future King of England, penned his Lepanto, a lengthy and by no means incompetent Spenserian semi-epic that lauded the ‘farreign papist bastard’ Don Juan while speculating that God might have granted him an even more resounding victory had his religious beliefs been more correct. ((King James’s Lepanto (not to be confused with Chesterton’s bombastic effort with the same title) was published in Scotland in 1591 and again in England soon after his accession there. One modern edition: The Poems of James VI of Scotland ed James Cragie (2 vols, Edinburgh, 1955-8). Find selected verses here))

The Rosary Feast

(Misinformation on this subject abounds, so it is worth considering at some length.)

This was instituted by Pope Pius V as the feast of Our Lady of Victory in the immediate aftermath of the battle of Lepanto on 7th October 1571, in recognition of the Virgin Mary’s role in interceding with the Father on behalf of the Holy League. The 7th fell on a Sunday that year, and the feast, soon renamed Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary, ((Our Lady of Victory had been the iconic Virgin of the Spanish reconquest. The Rosary devotion had been taken over from the Eastern Church in early medieval times. The two feasts, both well-established but neither as yet part of the official Roman calendar, were at this point in the process of amalgamating. Features of both were preserved in the ‘new’ Rosary feast, at which the Virgin Mary was celebrated as Help of Christians and nurturing mother, while (somewhat incongruously, and predominantly in places that had fought at Lepanto) retaining attributes of the ancient pagan war goddesses.)) was observed on the first Sunday in October until the early-twentieth-century reforms of the Sunday liturgy, when it was moved to the 7th.

Both Don Juan and Pius associated the victory with the petitions of the Rosary fraternities, which had been prominent (though not alone) in begging God and the Virgin for aid in the run-up to the conflict. Pius died the following year, and it was his successor, Clement XIII, who re-named the feast in 1573, in response to massive pressure from the Dominican order. Its founder, St. Dominic, was believed to have received the Rosary devotion directly from the Virgin, and the order has always seen it as its particular fief. ((Titian’s great fresco in the Rosary Chapel of the Dominican church of SS Giovani e Paulo (later destroyed by fire) showed the Holy League led by St. Dominic!)) Later the Virgin had appeared a second time to a Dominican friar, giving him an extended list of assurances to those who devoutly said the Rosary, among them that they would prevail over their enemies.

Rosary confraternities were by 1571 quite widespread in the West, the great majority being in Dominican establishments. Those of the City of Rome are said to have been processing en masse in St. Peter’s Square even as the battle raged, and Pius had certainly been leading Rosary devotions in Santa Maria Maggiore from an early hour. There may also be truth in the tradition that the papal legate’s pontifical blessing of the Holy League’s armada before the battle was prefaced with a massed recitation of the Rosary.

The new feast was initially to be kept only in churches with a Rosary confraternity and dedicated altar. (It was extended by degrees, eventually being declared universal in 1716.) But papal authority was taken lightly in the Holy Roman Empire, at least in matters of this nature, so it is quite conceivable that by the early 1600s the Rosary feast was being kept in the archducal chapel at Graz, despite the lack of a confraternity.

But Austria had played no significant part in Lepanto, being both land-locked unwilling to cancel the Empire’s non-aggression pact with the Turks. The Rosary feast will there have centred on the nurturing, rather than war-like, aspects of the Virgin Mary. For this reason (and also because there is no record of Viadana’s psalm settings being used at either Venice or Graz) we have played safe by locating our Vespers reconstruction in neither city, but in an unspecified North Italian location: one which we assume to have participated in the battle, and which will accordingly have observed the Rosary feast as an annual victory celebration. Regardless of where the seven-choir arrangement of Gabrieli’s Magnificat was made (at Graz? at Venice? at another of the Italian and Germanic courts in which Gabrieli’s music was admired?) there was frequent interchange of music between friendly courts, and such a uniquely large-scale and unashamedly bellicose Magnificat setting could have been eagerly sought by northern city-states that had fought at Lepanto, such as Florence and Genoa (whose rich maritime merchants had contributed private-enterprise galleys to the Venetian fleet).

Venice goes her own way

The Catholic Church at large ascribed the defeat of the Turks to the assistance of the Divinity, urged on by Our Lady of the Rosary, who was in turn responding to the solicitations of the faithful. But Venice, characteristically, went its own way. ((The new feast was certainly observed in Venice, though perhaps not in St. Mark’s or the cathedral. The Rosary confraternity in the great Dominican church of SS Giovanni e Paulo, the first of a vast number in the city, was formed in 1573, the very year of the feast’s renaming: but the Virgin of the Rosary will presumably have been celebrated there as nurturing mother rather than the Christian counterpart of the ancient pagan war goddesses, since the feast must always have taken second place to the state’s Lepanto commemoration on St. Justine’s day. There must, besides, have been an awkward conflict of interest every seventh year, when the 7th fell on the first Sunday and both the friars and the lay members of the Giovanni e Paolo Rosary confraternity will have been required to process in full festal rig to St. Mark’s. Nothing is known of the musical side of the feast at SS Giovanni e Paolo before the 18th century, by which time a considerable sum was being spent on the music at the High Mass.)) Venetian paintings commemorating Lepanto depict a variety of saints: Mary, Mark, and, above all, St. Justine (San Giustina) of Padua, an obscure early martyr with a mainly local following whose feast day fell on 7th October in the San Marco calendar.

The Republic had its own miraculous revelation of the victory, ((Recounted in Rocco Benedetti, Ragguaglio delle allegrezze, solennità , e feste fatte in Venetia per la felice vittoria…IN VENETIA, Presso Gratiosa Percaccino M.DLXXI.)) which (if it was not a pious invention) may even have preceded Pius’s celebrated vision in Rome. (Neither city, it is said, had any way of knowing that the far-distant battle was to be joined on that particular day.) It was presumably at around midday on the 7th that that an unnamed Carmelite monk, having celebrated Mass, turned to the congregation [il popolo] and announced: ‘Brothers, I tell you glad tidings. The armies have contended, and the Christians have been granted the victory. Rejoice, ascribe glory and honour to God, and continue to live your lives in holy fear of him.’ Having been apprised of the news, the Venetian authorities were as cautious as the pontiff, keeping it under their signorial hat until the first of the Holy League’s ships arrived to confirm the victory. ((That first arrival nearly replicated Theseus’ tragic error on his return to Athens from Cretan captivity. Trailing captured enemy flags, it was at first taken to be full of victorious Turks, but lamentation soon gave way to jubilation and the ringing of every church bell in the city.))

In the aftermath of the Holy League’s victory St. Justine was declared a major patron of the Republic, her little parish church near the cathedral of San Pietro ((The church was demolished in 1812, during the Austrian occupation that succeeded the Napoleonic conquest.)) was renovated, and her statue crowned the summit of the Arsenal’s principal entrance, directly above the Lion of St. Mark. Early on 7th October each year until the fall of the Republic doge and signoria made their way to the church of San Giustina for a Mass of Thanksgiving, accompanied by (probably only some of) the St. Mark’s musicians. Later in the day they sat in state in the quire of the ducal basilica while the parishes, convents, scuole and other ecclesiastical organisations of the city filed past in a series of magnificent processions. We have no record of how Vespers of St. Justine was observed in St. Mark’s, but it seems overwhelmingly likely that, on what was now a major Venetian feast, it will have been celebrated with elaborate music, ((For what it is worth, Benedetti (see footnote 8) enthuses – in the conventionally unspecific terms, unfortunately – about the music at the thanksgiving Mass of the Holy Ghost in San Marco on the Sunday following the 1571 victory, at which ‘se fecere concerti divinissima, perche sonandasi quando l’uno, equando [two words??] l’altro organo con ogni sorti di stromenti, e di voci, conspirarono ambi à un tempo in un tuono, che s’aprissero la cattaratte dell’harmonie celeste, & ella diluviasse da i chori Angelici.’ He also describes later nocturnal secular festivities around the Rialto bridge (for which it is not inconceivable that Andrea Gabrieli composed his Aria della battaglia for eight wind instruments, a notionally busked chunk of which is incorporated in my restoration of his nephew’s 7-choir Magnificat): ‘Da prima sera sino alle cinque di notte [10 p.m.? 11 p.m.?] di continuo s’udiva suono di tamburi, di trombe squarciate, e di piffari, e sopra i pergola [sic] diversi bei concerti di musica, e spessi tiri di codete, in modo, che’l luogo rassemblava la casa, e’l palazzo della Giocondita, e dell’Allegrezza.)) especially since the limited space in San Giustina will very likely have precluded any large-scale music at the morning Mass.

So, given (a) that Gabrieli’s Magnificat was manifestly composed for the commemoration of some great victory (from internal musical evidence: see below), and (b) that the annual Lepanto celebrations were by far the most likely of these in later-sixteenth-century Venice, I have assumed that Gabrieli’s original three- (or conceivably four-) choir setting will have been composed for Vespers (probably First Vespers) ((First and Second Vespers were celebrated respectively on the eve and on the day of a feast. St. Mark’s seems to have retained the medieval primacy of First Vespers, ignoring the Tridentine reversal of status.)) of St. Justine’s Day (7th October) at St. Mark’s, sometime around the year 1600 (i.e. in his full maturity as a composer but before his lengthy final illness made fulfilling his duties at St. Mark’s – and so, presumably, composition – impossible.)

Gabrieli’s Magnificat à 28, C150

The unique form

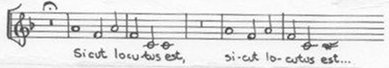

This setting of the Vespers canticle is unique (in both its lost original and surviving forms), and blatantly at odds with the strictures of the reforming mid-16th-century Council of Trent. Each of the first eight of the canticle’s ten verses is followed by a setting of an interpolated piece of text – what musicologists call a ‘trope’. The unique features are (i) that the same scrap of interpolated text is set each time, always differently, and always making prominent use of one of the most common Magnificat psalm tunes; (ii) that the scrap in question is the first half of Verse 10 of the canticle, ‘sicut locutus est ad patres nostros’.

As I argue below, the Magnificat very probably begins thus:

V1: Choir I Ã 4 (solo soprano and instruments)

The ‘sicut locutus’ trope (setting I): Choirs II, IV, VI in ‘four-part unison’

V2: Choir III Ã 4 (solo voice and instruments)

The ‘sicut locutus’ trope (setting II): Choirs II, IV, VI in ‘four-part unison’

V3: Choir V Ã 4 (solo voice and instruments)

The ‘sicut locutus’ trope (setting III): Choirs II, IV, VI in ‘four-part unison’

V4: Choir VII Ã 4 (solo voice and instruments)

The ‘sicut locutus’ trope (setting IV): Choirs II, IV, VI in ‘four-part unison’

V5: Choirs I, III, V, VII, notionally à 16

The ‘sicut locutus’ trope (setting V): Choirs II, IV, VI in ‘four-part unison’

There is much greater variety of forces in the ensuing verses, but the tropes continue to be given to the three unison cappellas. See The ‘sicut locutus’ tropes and the inserted battle music for the way the Verse/Trope pattern is dramatically broken after Verse 9, and for my account of the over-all form of the setting.

The reconstruction

With only the surviving Choirs I and II to go on, reconstruction of C150 has been a much more demanding task than was the case with its 33-part companion, C151 – one, indeed, that I tackled only sporadically over a fifteen-year period, and was eventually able to complete only with the vigorous encouragement and active collaboration of Robert Hollingworth. As with In ecclesiis, I do not claim to have retrieved what has been lost, merely to have produced a completion that is sufficiently Gabrielian to convey some notion of the splendour of the original. ((Any success I owe to the techniques of historical mimicry that were enjoyably and expertly inculcated as part of my traditional university music degree: something that is now in many places being abandoned as a supposedly sterile exercise.))

There can be no doubt that the ‘other’, 33-part, Magnificat, C151, (of which I produced a conjectural completion for Paul McCreesh’s Gabrieli Consort in 1999, recorded by them on Music from San Rocco on Archiv), is an expansion of a lost three-choir setting, since, in its original form, the Gloria Patri was clearly identical to that of Gabrieli’s three-choir Nunc dimittis à 14 in the 1615 Symphoniae sacrae. ((The two canticles will have formed a matching pair, for use at a combined service of Vespers and Compline – of the kind that inspired Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer Evensong, just as the monastic tradition of singing Matins and Lauds as a unit lies behind his BCP Matins.)) A four-choir arrangement of this entire lost Magnificat also survives (possibly by Gabrieli himself), so the reconstruction was a comparatively straightforward matter.

The present 28-part Magnificat, C150, has no such parallels (so the assumption that the original was for three choirs is a subjective judgement: it may have been for four). My reconstruction has therefore of necessity been based on a painstaking preliminary analysis of the surviving Choirs I and II, which has revealed a surprising amount about what is missing.

For example, one can often see the eight surviving parts deliberately, even awkwardly, avoiding figuration that would form forbidden parallel intervals with the leading part – the ‘tune’ – in one of the lost choirs. This can thus be reasonably confidently reconstructed, often in the highest sounding part.

A particularly helpful feature is the series of double echoes in the settings of Verses 6, 7 and 8 (see The double echoes, below.)

In many places one can see that the surviving music is complete and self-contained, most notably in the four-part writing of the successive settings of the ‘sicut locutus’ trope (interpolation), as notated in Choir II, a purely vocal ‘cappella’. Logically, these passages must either be for Choir II alone or for Choir II with one or two other choirs, identically constituted, operating in ‘four-part unison’. I have assumed that Choirs II, IV and VI are all cappellas, and that they sing the trope settings in unison but for the most part go their own individual ways elsewhere. (The 42 ½ bars of ‘sicut locutus’ settings means that a considerable portion of the Magnificat’s 202-or-so bars can be guaranteed Untouched By Reconstructer’s Hand.)

Conversely, the very bare eight-part writing in Choirs I and II in certain places – bereft of the major third, with internal doubling of parts, etc. – indicates that here is a multi-voice tutti.

Only for Verses 2, 3, and 4 is there absolutely nothing to go on beyond the rests in Choirs I and II, which indicate their lengths. Here I have been forced to compose ex nihilo – a total of 30 ½ bars. The fact that these three verses are entirely lacking suggests that four non-cappella choirs took Verses 1 – 4 in turn, especially since the writing in Verse 5 (in the surviving Choir I) looks as though these four choirs here came together: hence my assumption that the three cappellas (II, IV and VI) were complemented by four non-cappella choirs (I, III, V and VII) each comprising one vocal and three instrumental parts. (Remaining matters of speculation are the tessitura of these choirs and the voice-types of their solo singers: see Other assumptions…, below.)

The Magnificat begins on a deceptively small scale, only to expand inexorably later. Was this a sly ploy on Gabrieli’s part, to fool his listeners into thinking that the setting was to be short’n’simple? Or was it a calculated structural device? Both, probably.

(A major decision was whether there should be a total of five or seven choirs. A rival reconstruction has opted for five. For the reasoning behind my choice of seven, see the dauntingly lengthy section à 20 or à 28?, below.)

Other assumptions behind my edition

I have assumed that all seven choirs are four-part and that II, IV and VI are cappellas (see à 20 or à 28?, below). Choir I consists of a single solo ‘mezzo-soprano’ voice (C2 clef) and three instruments. What, then, of the three other non-cappella Choirs III, V and VII? With only instinct to go on here, I have assumed that that these were similarly constituted, with a solo bass in Choir III, a high tenor (notional C3 clef) in Choir V, and, in modern terms, a ‘baritone’ (notional C4 clef) in Choir VII. Following the assumed practice of the period, I deliberately did not think in terms of specific scorings when composing Verses 2, 3, 4, or in the reconstruction in general. That I have left in the capable hands of the conductor, Robert Hollingworth. (For the recording he has allocated Choirs I and VII to strings, III and V to wind; but he has – perfectly validly – preferred slightly different scorings for some concert performances.)

An admission

I must come clean about a possible shortcoming. Even though the three instrumental parts of Choir I have no text in the Graz MS, they have been composed with the text in mind, so that this could easily be entered beneath the music. This (or, indeed, the actual texting of instrumental parts) was standard practice, and had a multiple function. It ensured a cohesive over-all texture; it helped the instrumentalists match the phrasing and articulation of the singers; and it allowed for the ad lib addition of doubling choirs, which would almost inevitably be entirely vocal. (Even high G2-clef parts for cornett or violin would often be texted, despite calling for high A, or even B flat, which were outside the current soprano range. Praetorius explains that additional singers doubling such parts should be at the lower octave – an example of calculated ‘orchestration’ by means of octave doubling: cf Part-doubling, below.)

I have mostly followed the Praetorius line in the bigger tuttis, where an instrumental part will often be doubling a surviving sung part, or vice versa, at whatever octave. But elsewhere, for various reasons, I have not always supplied potentially textable instrumental lines. However, this may escape musicological censure if I am right in my instinct that the Graz expanded arrangement (not Gabrieli’s lost original) must date from some years into the seventeenth century: a time when composers were beginning to write independent, idiomatic instrumental parts in polychoral music of this kind.

Part-doubling

A feature that has acted as a major guide to reconstruction incidentally confirms that neither of the Graz Magnificat arrangements can be by Gabrieli himself. This is the liberal deployment of unison and octave doubling, which was a characteristic technique of ‘advanced’ 17th-century multi-choir music.

This operated at two distinct levels. An entire phrase may be doubled at the unison or at one (or even two) octaves, an authentic Gabrielian practice that is essentially the beginning of modern orchestration. Alternatively, there can be a constant, shifting doubling of short fragments – just a few consecutive notes. This is emphatically not orchestration, since the ear does not perceive it. It is a compositional technique that allows sonorous writing in many parts without recourse to the kind of awkwardly-skipping ‘dog’s-hind-leg’ kind of phrases to which even Gabrieli sometimes resorts in the effort to observe the scholastic proprieties. This type of fragmentary doubling is commonplace in the polychoral works of Monteverdi, Schütz and many others, ((To my knowledge, it goes mostly unremarked, and stands in urgent need of scholarly investigation. Andrew Parrott and I felt the lack acutely when working on some of the doubling instrumental choirs in sacred works by Schütz and Monteverdi. To supply lost parts or amend inaccurate ones, we were forced to grope blindly after the principles on which they will have been made.)) but rarely if ever to be found in those of Gabrieli, so the fact that it is to be found in the Graz Choirs I and II points to a non-Gabrielian arranger’s hand – especially since the doubling is in at least one instance within a single four-part choir, a crudity that would have made Gabrieli wince with pedantic horror. (He insisted that his pupils should master the art of traditional prima prattica polyphony before tackling the modern secunda prattica.)

The double echoes

Another technical feature that has made conjectural reconstruction easier is Gabrieli’s extensive use of double echoes in verses 6, 7 and 8. By great good fortune, either the statement of the phrase or one of its two echoings always survives in Choir I or Choir II. (In one case we have both statement and second echo.)

Gabrieli must here have been imitating Peri, who was the first to use double echoes in Arion’s great ship-board lament in the fifth of the 1589 Florentine Intermedi for La pellegrina. He is about to be cast into the waves by pirates, and Peri’s echoes are from the wind and the waves, and so progressively quieter and more distant. Gabrieli’s echoes are quite different. They mostly set angry, bellicose fragments of Magnificat text, and must therefore be consistently forte – though my reconstruction does progressively reduce the forces each time.

The ‘sicut locutus’ tropes and the inserted battle music

C150 is no run-of-the-mill setting of the Canticle of the Blessed Virgin, witness (a) the vehemence with which Gabrieli sets the bellicose verses, and (b) the ever-more-exultant, even gleeful, nature of his inter-verse tropes. These latter set the beginning of the final Verse 10 of the Magnificat, ‘Sicut locutus est ad patres nostros’, always in a kind of free up-dating of the venerable ecclesiastical prima prattica manner, and always making bold, in-your-face use of a standard Magnificat psalm tone as cantus firmus. ((It is odd that very little use is made of the psalm tone in the settings of the verses, whereas it features complete in every setting of the trope – which is only half a verse. I know of no comparable example, and wonder whether there may be some particularly arcane symbolism here.))

The complete verse reads ‘As he promised to our forefathers: Abraham and his seed for ever’. This will have been carefully chosen to reflect the occasion for which the original setting was made. The Magnificat was Mary’s response to Gabriel’s Annunciation, deliberately imitating the agèd Hannah’s song of thanksgiving when she conceives the prophet Samuel. In this final verse Mary is referring back to Genesis 15, where the God of her ancestor Abraham promises him that his seed shall be numberless, and that they shall constitute a chosen people. That quasi-legal covenant could only be broken if both parties abrogated it, and the Christian Church, deeming this to have occurred when the Hebrew hierarchy rejected Jesus as the Messiah, reassigned both promise and covenant to herself. Venice would here appear to be going one step further, treating the Abrahamic reference as prophetic of the Serene Republic’s supposed status as Protector of Christendom – a divinely-appointed role that had been triumphantly fulfilled at Lepanto. (Venice saw herself as having won the battle virtually single-handed, with a little assistance from the other League members and a great deal from God, St. Justine, St. Mark, and the Virgin Mary.)

Since one of the annual Venetian Lepanto commemorations is by far the most likely occasion for which Gabrieli’s original Magnificat was composed, the recurring half-verse trope is thus a repeated asseveration of Venice’s role in the victory. After each of the Magnificat Verses 1 – 8 this rings out in ever-varied settings (sung, as I argue above, by all three cappellas in ‘four-part unison’). Then comes something that is not uncommon in Gabrieli’s choral music yet must here have a special significance. After verse 9, instead of a ninth setting of the trope (which would awkwardly pre-empt the ‘Sicut erat’ of the immediately-following Verse 10) the choir books have a full bar’s rest in all parts, with cesurae (pause marks). After this comes a strikingly assertive setting of the opening of verse 10, now at last almost certainly given to the full forces. I perceive the ‘Sicut locutus est’ in seven of the eight parts of the surviving Choirs I and II as secondary to the bold, equal-note arpeggio figure in the one remaining part, which will surely have been duplicated in the lost choirs. It seems designed to stand out from the texture, and is surely calculated to evoke a military trumpet call:

Could the preceding bar’s rest have contained an actual trumpet call on the wind instruments ((I have regretfully ruled out the alternative possibility that natural trumpets will have been deployed at this point. Choirs of trumpets and drums did feature in festal polychoral music of the early seventeenth century, not least at Graz, where such a line-up (possibly with the trumpets two-per-part) formed one of the seven choirs of the mostly-lost Mass, Magnificat and Jubilate Deo that Valentini published in 1621. But the item immediately preceding the two Gabrieli Magnificats in the Graz choir books is a 20-part Magnificat ‘con le trombe’ by Reimundo Ballestra, so – logically – had a trumpet choir been called for in the present setting, that would surely have been similarly titled. As a matter of fact, the imitation of trumpets by wind instruments – and voices, for that matter – was part of the long-standing battle-piece genre. Most such works, including Andrea’s Aria, were in imitation of Clement Janequin’s famous programmatic chanson depicting La battaille de Marignan.)) which is here being echoed by full vocal and instrumental forces? Court instrumentalists will have been no strangers to genuine or simulated military signals, if only in battaglie, and most professional musicians of the time were accustomed to busking approximate versions of known works – to an extent that their modern counterparts would find hard to credit. I have therefore assumed that military music sounded during the notated pause, to accompany the parading of captured Turkish battle standards through the church.

As it it happens (and almost certainly by happy chance), the first phrase of a trumpet call by Cesare Bendinelli, ((Dr. Peter Downey has very kindly advised me on the use of this particular signal. It was not one of the traditional military calls, but one of Bendinelli’s own composition. It therefore had no hortatory import (Into your bunks! Make for the cook-house! Slaughter the enemy! or whatever) but would have functioned as a kind of call-to-attention, alerting the troops to whatever instructive call was to follow.)) published in the early 17th century, is an almost perfect match for Gabrieli’s ‘sicut locutus’ phrase. I have therefore plugged the gap with Bendinelli’s opening on massed wind, followed by a supposedly busked extract (the most celebrated little chunk, in fact) from one of the most admired works produced in the wake of the Lepanto victory, Andrea Gabrieli’s Aria della battaglia for eight wind instruments. And this I have allowed to segue into the beginning of Gabrieli’s Verse 10 in a way that I hope is not too fanciful and believe would have been well with in the improvisatory capabilities of first-rank players – with a little rehearsal.

The liturgical context

It is worth keeping this in mind as we listen. In the course of the Magnificat (the climactic item of Vespers) there will have been complex censings: of the high altar, of the individual robed clergy, of the musicians in their various galleries or platforms, and (in St. Mark’s or any other princely chapel) of a long series of nobles, state officials, attendant ambassadors and the like, besides the communal censing of the people. Even at a normal Vespers service the Magnificat censings could take so long that the musicians would stand ready to repeat verses from the beginning of the canticle if necessary, or else the organist would improvise until the censings were complete and the Gloria Patri could be begun.

In the present case, we may imagine that by the time Bendinelli’s trumpet call rings out the entire church will have been filled with fragrant smoke (as at the dedication of Solomon’s Temple), and the effect of the Turkish banners being paraded in this heady atmosphere will almost inevitably have been enhanced by the al fresco pealing of church bells and discharge of small-arms and cannon. From Gabrieli’s Verse 10 to the conclusion, all is tutti triumph, and we may visualise the Turkish banners ranged (or humiliatingly lowered?) round about the high altar. ((Surprising numbers of such banners remain – at least on display, if no longer ritually paraded – in churches of the Holy League participants. Goethe saw the Venetian banners still on view at St. Justine’s church in Venice in 1786, by which time the time-honoured celebration would seem to have become something of a shadow of its former self. In a recent gesture of inter-faith friendship, the Vatican returned its own not inconsiderable collection of banners to Ankara.))

This kind of ritual can hardly have obtained at Graz, since Austria had played no part in the Lepanto sea battle. So in the archducal court chapel the crucial bar’s-rests-with-cesurae may simply have been silences: unless the seven-choir arrangement had been made – or adopted – for some non-Lepanto military commemoration: see below.

Seven-choir settings

Seven choirs seem to have constituted the ne plus ultra of polychoral extravagance. I can think of no setting for an unambiguous more than seven. ((The eight x five division of forces in Tallis’s Spem in alium is basically a compositional convenience, the true division being into four choirs of ten. Equally misleading is the 10 x 4 division in Tallis’s 40-part models, Striggio’s Ecce beatam lucem and Missa Ecco si beato giorno, the former boasting an endless variety of subdivisions, the latter being divided into five choirs of eight. Works for more than six choirs by the Colossal Baroque composers of Counter-Reformation Rome and the Germanic countries generally prove to be musicological chimeras. An example is the supposedly twelve-choir Mass by Orazio Benevoli that he directed one Ascension Day in mid-century St. Peter’s, the twelve choirs representing the twelve Apostles. (I take it that the one placed at the internal summit of Michelangelo’s dome stood for St. Peter.) The music does not survive, and – disappointingly – it is now reckoned that this was actually a six-choir setting with the choirs doubled in a way that was common in Rome, Venice and elsewhere.)) There were plenty of works for four, five, even six choirs in early-seventeenth-century Italy and (especially) the Germanic countries, but those for seven may have had a particular, perhaps cosmic, significance. Giovanni Valentini’s seven-choir Magnificat, Mass and Jubilate Deo, published in 1621 (only two parts surviving), are in a distinctive Germanic festal genre that involves a choir of natural trumpets and drums, the trumpets at least on occasion playing two-per-part. Similar forces were called for in the lost Magnificat that Schütz apparently composed for the Reformation centenary celebrations in Dresden in 1617.

The number seven has a plethora of symbolic connotations, most obviously the seven planets and the seven days of Creation. If the seven-choir arrangements of Gabrieli’s two Magnificats were made at Graz, the number could have been symbolic of the seven electors (who voted for the emperor), and they could date from any time between the older Ferdinand’s creation as Archduke of Austria in 1595 and his son’s accession to the imperial throne in 1637. The most likely arrangers are Priuli and Valentini (see The two seven-choir Magnificats, below); for significant occasions (accessions, marriages, and Austrian victories in the Thirty Years’ War) see the TABLE of significant dates…, below).

The two Gabrieli Magnificats – à 33 (C151) and à 28 (C150)

The seven-choir Magnificat on our recording is one of a pair attributed unambiguously – but misleadingly – to Gabrieli in an early-17th-century manuscript source deriving from the chapel of the archducal court at Graz, second city of Austria.

We know that C151 must have begun life as a triple-choir companion to the 1615 triple-choir Nunc dimittis à 14, with the Gloria Patri in common; the 1615 Symphonia sacrae also contains a Magnificat à 17 (C83) that is another four-choir arrangement of the lost triple-choir original of C150: presumably Venetian and conceivably by Gabrieli himself. Whether the original of ‘our’ Graz Magnificat à 28 (C150) was for three or four choirs is a matter of speculation: I incline towards the former.

SOURCE: A-WN Cod. 16708, a pair of MS choir books, the first two of an original set of seven which was copied at Graz sometime in the early 17th century for the chapel of one of the two future Emperors Ferdinand, father and son (see TABLE, below). The Contents pages unambiguously identify the two adjacently-copied large-scale Magnificats as ‘Joannes Gabrielis’ (‘Joann Gabrielis’ at the head of the music in each book). C151 is unproblematically à 33, but C150 has conflicting designations, essentially identical in the two choir books:

on the Contents pages: Magnificat a 28. Con il Sicut locutus est. In Ecco

on the title pages before the music: Magnificat Con il Sicut locutus est. A.20. In Ecco

at the head of the first pages of music: Magnificat A. 20

These neatly copied and impressively accurate choir books contain the music for Choirs I & II of a large number of polychoral works, many of them by composers connected with one or both of the two Ferdinands. Many are for double choir, and so complete. Few are known to survive elsewhere. Several are by two gifted Venetian-born musicians, Giovanni Priuli and Giovanni Valentini: organists, choir-directors, composers, followers (and very likely pupils) of Giovanni Gabrieli, (Following Priuli’s death in 1626 Valentini succeeded him as Kapellmeister at Graz Both men served under the two Archdukes, the future Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II and his son Ferdinand III, during their periods as Archdukes of Austria at Graz. For these and other possible arrangers see Who arranged the two seven-choir Magnificats?, below.)

Is C150 à 20 or à 28?

(The two Magnificats are demonstrably arrangements of lost originals, and both, I firmly believe, are for seven choirs. Since a rival reconstruction of ‘our’ setting, C150, has recently appeared for five choirs, only one of them a cappella, I need to fight my corner in no-doubt wearisome detail.)

Following the usual (though strangely unhelpful) practice of the time, the Graz choir books give only the total number of parts in each work: nowhere is there any indication of the number of choirs into which they are divided. In the case of ‘our’ Magnificat, C150, Choirs I and II are both à 4, and I have for several reasons assumed that the remaining choirs are also four-part. But in view of the conflicting designations A20 and A28 (see above), are we to assume five four-part choirs (5 x 4 = 20) or seven (7 x 4 = 28)?

The fact that the designations vary identically in the two choir books (‘A28’ on the Contents pages, ‘A20’ in the two other places) decreases the likelihood of a scribal slip, the more so since the unknown copyist of these books (and, no doubt, of the missing five others) everywhere shows himself to be exceptionally conscientious, accurate and practical-minded. We therefore need to investigate further before dismissing ‘A20’ – twice – as a copyist’s aberration.

The obvious first step is to look for other dual designations. These are not too hard to find: in fact, there two examples in these same choir books. A third item could well have had a dual designation, Giovanni Gabrieli’s Magnificat C79, for two five-part choirs. Another manuscript source elsewhere derives from these a rather curious additional four-part choir, which reproduces verbatim three parts from one choir and one from the other, none of them a bass. Had the Graz scribe been copying from this source he would no doubt have relegated the derived choir to choir book III and given the setting a dual designation, probably ‘A14’ on the Contents pages, ‘A10’ elsewhere.

The first of the extant examples is a Magnificat by Bartolomeo Sponton. This has the designation ‘A8’ on the Contents and title pages of both surviving books, and the music for the two four-part choirs is entered in choir books I and II in the usual way. But the doxology is headed ‘Gloria Patri a 13’. The inference is clear: a third, five-part choir must have joined I and II for this final section, its music in the now-lost choir book III. There is nothing very surprising about that, but it is relevant to the more puzzling dual designation of the final work in these choir books, Marenzio’s supposedly double-choir, nine-part setting of the Te Deum. ((It is published in Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae 72 Vol 3))

This has been taken to be a straightforward nine-part setting, despite being headed ‘A13’ on the two Contents pages and on both title pages in this, its only source. ‘A9’ is to be found only once, at the head of the first page of music, on the left-hand page (f.216r) immediately above the C1 Cantus part.

Now the scribe usually provides head-of-the-first-page-of-music designations, but when he does so it is consistently in both choir books. So why is there no such indication for Marenzio’s Choir I? The music (Verse 2 of the hymn, this being an alternatim setting) points us towards the answer.

To ferret out the reason for the scribe’s puzzling heading, we need to visualise the physical conditions of a typical church performance of the period, bearing in mind (a) that ecclesiastical singers nearly always sight-read their music, and (b) that the chapels of leading Catholic courts took considerable pride in immaculate presentation. As with court theatres, standards (in this case, the conduct of every aspect of the liturgy) were seen as directly reflecting the standing of the ruler, and a thoughtful scribe would seek to forestall any embarrassing contretemps in the singing by inserting what we might call cautionary rubrics. The Graz scribe will have been a member of the archducal Kapelle himself, and aware of the kind of minor mishaps that can occur in the best-regulated set-ups.

Choir II of Marenzio’s Te Deum will typically be standing in its own separate gallery or platform, with no access to the music of Choir I. Having heard them sing the first half of the verse, followed by the conventional – and often quite protracted – mid-verse pause, Choir II would most naturally assume that the second half of the verse is theirs alone, to be begun by their own sub-conductor – were it not for the scribal designation ‘Ã 9’. The designation is therefore not a description of the setting as a whole but a cautionary rubric applying to the second half of this verse. It alerts the Choir II sub-conductor to look out for his counterpart in the Choir I gallery/platform (who will always be visibly giving or relaying the beat) so that they begin the second half together. After this initial verse, repeated warnings are hardly necessary, since the sub-conductors will be aware of the possibility of irregular combinations and alternations of choirs (which do, indeed, abound throughout this unusually varied Te Deum setting). So, even though the second contrapuntal verse (Verse 4) is also set for Choir I (first half) followed by both choirs (second half), the scribe has felt no need to repeat his cautionary rubric.

But if the single ‘Ã 9’ indication is merely a warning to the singers, we have still to account for the work’s designation ‘Ã 13’ on the Contents and title pages of both surviving choir books. The music for the even-numbered verses is self-sufficient as it stands, and the clefs of the four-part higher Choir I (C1/C2/C3/F4 clefs) show that this is not a cappella, which (at least in passages in which it fulfilled a characteristic ‘binding’ function) might conceivably be doubled at will to give a notional total of thirteen parts.

Nonetheless, there is a remote possibility that Choir I might be doubled in any case: if, for example, its music was sung by two identical choirs of four solo voices, which were pitted against a weightier Choir II (C2/C3/C4/C4/F4 clefs) with several voices per part and/or doubling instruments. That solution might explain the otherwise unnecessary designations ‘trium’ and ‘quattuor’ at two places where Choir I sings alone (the three-part first half of verse 18 and the four-part complete Verse 20). The implication – again for the benefit of the sub-conductor(s) – would not be that solo voices are intended here (since Choir I will consist of solo voices in any case) but that the doubling voices of Choir III are silent in this verse, with the music no doubt omitted from their now-lost choir book III.

But that explanation is far-fetched. A much simpler one is that the lost choir book III contained the music of a third choir, which sang the odd-numbered verses – the verses which in an alternatim setting like this would normally be sung to plainchant.

The snag is that no comparable setting of the Te Deum is known, though one could point to certain Spanish settings of c. 1500 which go against standard practice in a different way, calling for a single polyphonic choir and two separate chant choirs, each choir taking every third verse. Might Marenzio here be deliberately setting his face against the usual (and frequently dull) kind of polyphony-alternating-with-plainchant Te Deum? His settings of the even-numbered verses are unusually enterprising, with expressive madrigalian touches, and it would seem to me perfectly possible that he was also breaking with tradition in a second way, by providing settings of the verses that would normally be chanted: perhaps because this Te Deum was for some particularly grand occasion; or perhaps he simply wished to do full justice to the splendour of the venerable text.

My hunch would be that Marenzio’s lost Choir III would be a four-part, cappella-like line-up, featuring the Te Deum plainchant either as a long-note cantus firmus or treated in some freer manner. And the mould-breaking provision of music for the odd-numbered verses would not prevent any choirmaster from substituting the unadorned chant if he wished. That possibility could explain the one small remaining puzzle: since a lost Choir III would have begun the Te Deum (after the initial plainchant incipit), why was its music not entered in choir book I, with that of the two surviving choirs in II and III? If the polyphonic odd-numbered verses were explicitly ad lib. (more accurately, ad placitum), that would seem to a sufficient reason for its relegation to choir book III. But perhaps, in any case, the scribe already knew as he entered the setting that the Graz choirmaster would prefer simple plainchant.

Tortuous and speculative as the above arguments may be, they are sufficiently plausible to give us pause. There are only three dual designations in these exceptionally carefully copied Graz choir books. If two of the three are susceptible of perfectly rational explanation – the one self-explanatory, the other perfectly plausible – we should surely hesitate before making a rule-of-thumb judgement that the scribe’s four-times-repeated ‘A28’ designation for our Magnificat, C150, is an error.

In the case of that work there is a different, but equally straightforward, explanation for the A20/A28 dichotomy: that there are three cappellas, Choirs II, IV and VI, and that these are allotted identical music in all the ‘sicut locutus’ tropes, while functioning as independent choirs in at least some of the remainder. That would surely have been enough for the scribe to have thought of the setting as in one sense à 20 (because the three cappellas so frequently sing in ‘four-part unison’, notionally reducing the over-all total by 8), in another sense as à 28 (because they are equally frequently independent).

The pedant will instantly object to this reasoning on the grounds that the only ‘A20′ that results from the three cappellas’ singing in four-part unison is that of the silent Choirs I, III, V and VII. However, we are dealing not with a mathematical exercise here, but with a scribe’s instinctive designation, which would be quite clear enough to jog a choirmaster’s memory as he decides whether to select the Magnificat for use in service: ‘Oh yes, that setting, the 28-part one in which the three cappellas combine for the tropes.’

Who was the arranger?

It would seem reasonable to assume that the same person arranged both Magnificats, given that neither is known from any other source. (The fact that they are adjacent in the Graz choir books is irrelevant, since the items are there arranged in ascending number of parts, and these are the two amplest.)

There is one striking similarity of approach, as a table showing my assumed choir layout shows:

| C151 Ã 33 | C150 Ã 28 | |

| {Choir I Ã 5 | Choir I Ã 4 | |

| {Choir II Ã 5 | Choir II (cappella) Ã 4 | |

| Choir III (cappella) Ã 4 | Choir III Ã 4 | |

| Choir IV Ã 4 | Choir IV (cappella) Ã 4 | |

| Choir V (cappella) Ã 4 | Choir V Ã 4 | |

| {Choir VI Ã 5 | Choir VI (cappella) Ã 4 | |

| {Choir VII Ã 5 | Choir VII Ã 4 |

In both arrangements the inferred layout of choirs is ‘palindromic’, and the cappella choirs (two in C151, three in C150) sing in ‘four-part unison’ when the remaining choirs are silent. ((In the case of C150 this means Verse 10, ‘Sicut locutus est’ (here set conventionally). Choir book III is of course missing, but the entire verse may be taken verbatim from the anonymous four-choir arrangement of the same lost three-choir original. There verse 10 is given to the single four-part cappella, and clearly represents Gabrieli’s unaltered original. The expansion of this section to eight parts in the completion I made for Paul McCreesh is effective enough, but was wished on me against my better judgement.))

On the other hand, there are significant differences. In C151 the surviving Choirs I & II are both à 5, and in many places they operate as a unit, displaying a a technical device that is both fascinating and, to my knowledge, unique. The single texted (and therefore vocal) part in Choir I is frequently doubled by an untexted (and therefore instrumental) part in Choir II; and vice versa. ((I have assumed that he same device operates in my restored Choirs Vi and VII.)) The implication is that the two choirs, despite operating mainly as a unit, are to be placed a certain distance apart, to exploit a curious acoustic phenomenon: that two sources of the same sound operating at a reasonable distance sound louder than the same forces standing together. ((The phenomenon in this case affects only the doubled parts, but it works equally well for identical bodies, so that a choir of 400 can sound louder – and sometimes clearer – if standing as two choirs of 200.)) The two solo voices are thus ‘brought out’ even more effectively than they would be by the normal polychoral technique, by which the singer of the texted solo part within a given choir (or, where all is texted, the presumed ‘leading part’) is to be doubled by an instrument standing alongside, the remaining parts being purely instrumental. (Where a choir has two sung parts, much the same applies.)

This possibly unique ‘opposite-choir’ doubling technique in C151 points to an arranger of considerable skill and some subtlety of mind. I see no such evidence in ‘our’ 28-part setting. It would be absurd to suggest that its straightforward division into five four-part choirs may similarly reflect a less subtle mind; but it is undeniable that there are occasional crudities of part writing in the surviving choirs of C150 that have no counterpart in those of C151.

So was there a single arranger, or were there two? We cannot be certain, but I suspect the latter. There are, in any case, two prime candidates in the Graz archducal chapel, both followers and possible pupils of Gabrieli: Giovanni Priuli and Giovanni Valentini. (I am not in a position to question Steven Saunders’ informed judgement ((In Cross, Sword and Lyre: sacred music at the imperial court of Ferdinand II of Habsburg (1619-1637), Oxford, 1995.)) that Valentini is a rather ‘less polished’ composer than Priuli, but – as he demonstrates in his book – both were very considerable talents.)

From this point, for the sake of simplicity, I confine my speculations on authorship to ‘our’ Magnificat expansion, C150. If either Priuli or Valentini were indeed the arranger, then two imponderables stand in the way of a decision between them: we do not know whether the expansion was made for San Rocco or for Graz; and we do not know the precise date of the Graz choir books.

If the seven-choir expansion was made for Venice, then the Scuola Grande di San Rocco was the most likely location. One of the richest, and certainly the most musically active, of the major Venetian charitable confraternities, it was on more than one occasion reprimanded by the signoria for its extravagant spending on music, and would seem to have taken a particular delight in sheer scale. Its annual patronal festival on 16th August was marked by sumptuous music at the morning Mass in the scuola’s chapel and – even more – at the extended afternoon concert in the vast and glorious Tintoretto-adorned upper room of what Americans might call their adjoining frat house.

Gabrieli was in over-all charge of the music at San Rocco from at least 1595 until his death in 1612, though his kidney stone would have precluded active participation in the last nine years or so of his life. In 1604 and 1608 we know that seven organs were hired for the afternoon concert, and the connection has frequently been made between this and the two seven-choir Graz Magnificats. ((See Appendix III for the famous description of the 1608 concert by the English traveller Thomas Coryat, who was astounded by the scale of the music, the virtuosity of the singers, the size of a great-bass viol, and the ‘seven organs standing all in a row’. It has been suggested that what Coryat unknowingly attended was a Second Vespers of St. Roch, mainly because the Great Room has an impressive altar at the east end: but there are good reasons for believing it to have been a concert.)) That is an attractive idea, though there is no particular reason to assume that seven organs implies seven simultaneous choirs.

If the arrangement was initially made for San Rocco, then Priuli would be the likely candidate. He was responsible for the music at several of their St. Roch’s Day concerts around 1600, and upon Gabrieli’s death a few days before the 1612 festival took over at minimal notice to produce what was virtually a tribute concert to The Master. He could have taken both seven-choir arrangements with him when he moved to Graz.

Priuli entered the Graz Hofkapelle of the first Archduke Ferdinand (the later Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II) in 1614/15, staying on as the younger Ferdinand’s maestro when his father moved (with his Kapelle) to Vienna on becoming emperor in 1619; he died in 1626. So if Priuli did not bring the seven-choir arrangement with him from Venice he could have been commissioned to make it at Graz.

Valentini was almost certainly too young to have received such a commission in Venice before his departure to the court of Sigismund III in Poland in 1604/5. He joined the Graz chapel of the younger Ferdinand as organist at around the same time as Priuli, whom he succeed as maestro upon Priuli’s death in 1626. Valentini could therefore have made the expanded arrangements at Graz at any time after 1615 – but only if the choir books were copied after that date. Alas, they have only been dated to ‘the early seventeenth century’, which allows a great deal of leeway. Supporting the case for Valentini’s authorship are the seven-choir Magnificat, Mass and Jubilate Deo which he published in 1621, though these were in a rather different, Germanic genre, with one of the seven choirs consisting of trumpets and drums (see above). Only a repeated-note trumpet part and the Tenor of Choir II survive, so stylistic comparison is impossible.

The question arises, why would either archduke wish to commission or acquire the seven-choir Gabrieli Magnificats? Well, to begin with, both of them hugely admired Gabrieli. The elder Ferdinand is even thought to have deliberately delayed appointing a new court organist in order that the Venetian should be forced to extend his stay at Graz by several months and play at his patron’s first wedding, in 1601. Moreover, the Austrian Habsburgs deliberately used mammoth-scale polychoral music to boost their status, and it has been suggested that a seven-choir Habsburg arrangement could have been be symbolic of the seven electors who voted for the emperor.

A prime example of large-scale Habsburg polychorality is the Currus Triumphali Musici of the Lutheran composer Andreas Rauch, domiciled in Sopron, just over the Hungarian border, since the elder Ferdinand’s mass expulsions of Protestants in 1626 and 1627. The print consists of thirteen polychoral settings, ((Like our Magnificat, many of these have dual designations, the one exceeding the other by four or five (eg “ab 8. & 12. v”;”a 9. & 14.”): but I cannot ascertain the significance of this, not yet having seen the music. The title and Contents pages are reproduced in Andrew H Weaver, ‘Piety, Politics and Patronage: Motets at the Hapsburg Court in Vienna During the Reign of Ferdinand III (1637-1657)’ Yale University, 2002)) one dedicated to each of the Habsburg emperors to date, the last and largest having been composed for a ceremonial Entry into Sopron by the younger Ferdinand some years previously. (There is an outside chance that Rauch was himself the arranger of the two Magnificats, commissioned from him in his not-too-distant place of religious exile.)

What may be a crucial question is: what would either archduke have made of the obviously bellicose nature of ‘our’ Magnificat, let alone of its repeated ‘sicut locutus’ tropes? Both features could have made sense in the wake of some major military victory, the ‘chosen people’ connotations of the ‘sicut locutus’ tropes being as easily applicable to the German Habsburgs as to the Most Serene Republic. Here again the unknown date of the Graz choir books is a factor, but if they were copied as late as 1621 or 1622 C150 could have been embraced precisely because of its two peculiar features. In 1620 the Austrian forces won the first of their major victories over their Protestant opponents in the Thirty Years’ War, which had begun two years earlier with the famous but non-lethal Defenestration of Prague. In 1621 the younger Ferdinand became Archduke of Graz, his father having become emperor. 1622 saw the second marriage of the new emperor. In those early days of Austrian successes in the war, both Ferdinands saw themselves as doughty warriors for the True Faith, the Catholic cause seemed eminently winnable, and the accumulating defeats of its later stages were unimaginable: so, with the White Mountain victory dominating the Austrian self-image, any one of those three occasions could have been marked by a mammoth militaristic Magnificat. Austria, like Venice, could have seen itself as inheritor of the Abrahamic promise and a Champion of Christendom; deeming a military interpolation (like ours in the present recording) entirely appropriate.

But there remains the considerable difficulty that both Magnificats are in a set of choir books that was copied for the archducal chapel at Graz, and not for Ferdinand II’s quite separate imperial chapel at Vienna: and the White Mountain victory was emphatically the father’s, not the son’s.

In ecclesiis

In pursuit of the original version

Of all the items in Alviso Grani’s posthumous Symphoniae sacrae (1615), In ecclesiis is one of the most obviously defective. It has been quite severely cut down from the lost original version, with (for example) a second vocal line patently missing from great stretches of characteristic Gabrielian duetting solo voices against an instrumental background. The cutting-down has been competently done, for the most part, though the result is scarcely a match for the original conception. But Gabrieli’s division into four balanced choirs has been lost, with only the vocal cappella, his Choir II, remaining intact; and modern editors have entirely failed to see the problem.

We are all of us mesmerised by the notes on the musical page, so it is perhaps no surprise that the cut-down motets in the 1615 print have been performed by the most historically aware performers without a suspicion crossing their minds that anything was amiss. I have myself repeatedly sung, listened to, even produced for radio, the two most brutally curtailed motets (In ecclesiis and Quem vidistis, pastores?) in blithe unawareness of any problem. Worse, academics have seized upon In ecclesiis as the premier example of Gabrieli’s supposedly moving with the times, his two solo-voice-and continuo ‘choirs’ being cited to generations of music students as emulation of the sparer writing of younger contemporaries such as Monteverdi.

Had they looked more closely, these commentators would have been struck by an inexorable accumulation of anomalies. To take the most glaring example, the single solo voice of Grani’s Choir III enters at bar 145 with the words ‘libera nos’ after two bars for the Choir IV continuo alone, yet he should obviously be responding to the same phrase a fifth lower: so obviously that the most tyro Choir IV continuo organist will automatically play the missing phrase in the right hand:

All credit to Paul McCreesh, who was the first to intuit that several of Gabrieli’s large-scale motets in the 1615 print must be cut-down versions of what the composer had written. He commissioned me to expand the most skeletal example of all, the superb Christmas motet Quem vidistis, pastores?, and as I worked on this it quickly became evident that the cutting–down process could only have been effected in the most brutal way, with all parts deemed inessential physically jettisoned.

Reduced versions of this type will no doubt have been made for some of the innumerable occasions on which the San Marco singers and instrumentalists were hired to enhance (typically) the patronal festivals of Venetian institutions with limited space and/or finances: scuole, parish churches, nunneries and the like. They may have been a practical expedient during Gabrieli’s protracted and extremely painful last illness, when he was unable to fulfil his duties at San Marco, and will scarcely have been up to undertaking composing commissions. When the San Marco trombonist and composer Alviso Grani came to edit the Symphoniae sacrae after the composer’s death the jettisoned parts must have been lost, and he may not even have realised that he was in some cases publishing reduced versions.

For some reason, McCreesh later came to believe that what Grani got hold of were Gabrieli’s preliminary sketches, rather than cut-down versions, but I am quite certain, from the hands-on experience of making the restorations, that his first idea was correct. (As I remark in the liner notes of the present recording, it has often felt as though the clinically excised parts were hovering somewhere just behind me as I worked, awaiting resuscitation.)

Robert Hollingworth has recently suggested that a puzzled (and puzzling) observation by Michael Praetorius would seem to add authoritative back-up to McCreesh’s original surmise. Writing in Book III of his Syntagma Musica (1618), he refers to additional parts for complementary choirs, made up from the parts in the existing ones, ‘such as I have seen many times and in various forms notated in several of Giovanni Gabrieli’s concertos [i.e. sacred motets]; which, however, are not included among those which have appeared in print in recent years’.

On the face of it, Praetorius is saying that subsiduary choirs, which he had seen notated when in Venice, are lacking from (presumably) the 1615 print. But this makes little sense. As he well knew, such subsiduary (loosely, ‘doubling’) choirs were routinely devised by individual choir directors, according to size of venue and availability of forces. What would have been surprising would have been their inclusion in a musical print of polychoral music, not their omission. It looks as though Praetorius has misremembered, and that what had in fact struck him about certain Symphoniae sacrae items was the loss of many of Gabrieli’s original parts, Quem vidistis being the most egregious example, with In ecclesiis following it a close second. ((It is worth remembering that neither Grani nor Praetorius is likely to have seen, or made, a score of the works under consideration, and it is easy to become confused when dealing with a great number of separate parts.))

Working back to something like what the composer wrote does not necessarily call for any particular clairvoyant powers. Take, for example, Choirs III and IV of In ecclesiis in what I take to have been their original guise: two solo voices (which would normally be doubled by instruments) plus three (conceivably two) independent instruments. As I explain above, one of the singers and the ‘inside’ instruments were removed, leaving only voice and bass. But such lost vocal lines are often easy to recover, especially in characteristic Gabrielian passages where the two voices take the lead, duetting in imitation or near-canon – and once this is done, providing plausible replacements for the remaining ‘inside’ instrumental parts is a fairly mechanical exercise. ((I simplify: it is by no means always the vocal parts that are the ‘leading parts’ in Gabrieli’s polychoral music: instruments frequently share in the primary imitation, or carry the principal melody, with voices reduced to providing a superior kind of ‘filling-in’: but the principal remains the same in such cases.))

A particular problem in reconstructing In ecclesiis is that the ends of some of the performers’ parts from which Grani worked must have been defective, either badly stained or torn, so that he was forced to invent what was missing. This he did (with a few tell-tale solecisms which have hitherto remained undetected and uncorrected) under the misapprehension that the motet was scored for three choirs: one of four vocal soloists, one a four-part vocal cappella, and one of six instruments. His multiple confusions have been compounded by all modern editions of the motet, which err in one of two directions (see TABLE, below].

Some editors correctly assign two of the solo singers to Choir I and retain the cappella Choir II, but shoehorn the remaining two solo voices into the anachronistically minimalist Choirs III and IV to which I refer above, each comprising a mere solo voice and continuo. This produces near-intractable problems of balance (for which recording engineers are routinely called upon to compensate with close-miking.)

Other editors follow Grani in making the four solo voices of the 1615 print an independent choir: an excusable error, since he was almost certainly not working from score, but the result is grotesque. Far from forming a discrete choir, the four singers operate as a unit for precisely four bars towards the end of the motet. Such editions compound the practical difficulties presented by barebones textures and skewed balance, encouraging conductors to place the performers in a way that is at audibly at loggerheads with the way the antiphony operates.

The table below shows the layout of parts in different edtions. (Click for a larger version)

The proof of even musical puddings is in the eating. With the solo voices correctly allocated and Choirs III and IV restored (however inadequately) to what I believe was their full five-part richness, difficulties of balance dissolve away and the rich-hued splendour of the original is recovered.